Hasty marriage or open-ended courtship: What do anti-corruption & peacebuilding communities need?

- Lara Olson, CJL

- Jul 21, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 27, 2022

By Lara Olson, Independent Consultant, International Peacebuilding and Conflict Sensitive Development and Cheyanne Scharbatke-Church, Co-Director, CJL

The confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers in the heart of Calgary is known for many things. Beauty, history, spiritual importance to Indigenous people, but a setting for peacebuilding conversations? Not really. Yet this is where we—two practitioner-scholars specializing in fragile and conflict affected states—call home. So it was a rare pleasure to walk along the Bow while having animated discussions about anti-corruption and peacebuilding—and whether integration, essentially a marriage, of these fields is possible.

These wide-ranging conversations were catalyzed by the Berghof Foundation/U4’s Breaking the Vicious Cycle, a report advocating the integration of anti-corruption measures into peace processes. Lara, a peacebuilding scholar-practitioner who specializes in the post-Soviet states, has recently completed her doctorate examining how international approaches to civil society impact local civic networks and their ability to restrain violence. Cheyanne started in peacebuilding and after years working in Sub-Saharan Africa and the former Yugoslavia her focus narrowed in on corruption. Our similar but different backgrounds generated lively discussions that revealed biases, insights, assumptions, and ultimately reflections that went far beyond the Berghof Foundation/U4 report on what the most effective relationship between these two fields might be, and how to get there.

Arranging a marriage

The central theme in Breaking the Vicious Cycle is challenging the “de facto division of labour and sequencing” of the peacebuilding and anti-corruption fields whereby “mediators first aim to end violence and reach a peace agreement while anti-corruption actors come in later in to address issues of accountability and governance.” Numerous arguments resonated with both of us, including the emphasis on a systems approach to understand the conflict-corruption nexus and “enriching do no harm” by integrating a corruption sensitivity approach into peacebuilding activities to (at a minimum) deconflict these interventions.

Where the discussions got even more interesting was where we didn’t agree or didn’t understand each other. We found ourselves musing about “integration,” widely understood in organizational theory as on the maximalist end of the spectrum of collaborative relationships. This felt ambitious given the state of mutual understanding, relationships or trust required for such a close union. Are other looser relationships between these domains possible and perhaps even more effective for both agendas? And while the vicious cycles between conflict-corruption are clear, and an initial few dates between these communities have gone well, the idea of “integration” still feels like a big leap to ‘forever together.’

WHAT “anti-corruption” is on offer?

As our conversation unfolded, we realized that the source of many of our disagreements—likely resulting from our different backgrounds—were divergent understandings of what exactly was to be integrated into peacebuilding. In other words, what is the field of anti-corruption? Without a common understanding of its goals, key concepts (e.g., accountability), tools and approaches to international-local power dynamics, the peacebuilding audience is left to its own preconceptions as to ‘what’ is on offer. It is highly likely that each field has perceptions (and maybe even unhelpful stereotypes!) about what the other does.

For several years the anti-corruption community has questioned its own approaches and models, with a consensus slowly emerging that the principal-agent model alone is of limited utility in contexts of endemic corruption. However, this old school, often technocratic and apolitical approach is still how the field is perceived by many external to it. Our conversation suggests that peacebuilders need greater clarity about today’s anti-corruption field. After all, the point of a courtship is to get to know each other.

Accountable to “WHOM”?

At the heart of much of our discussion was the theme of who. Who should “decide” what this relationship looks like? To whom are these decisions accountable?

We both knew full well that macro models for liberal peacebuilding have largely failed over the last two decades for many reasons, one of which being the widely acknowledged ‘top-down’ nature. So, who must any “more integrated” agenda be driven by and remain accountable to? What role will local peacebuilding and anti-corruption activists have in determining if, when and how this integration is actioned in their context?

"While the vicious cycles between conflict-corruption are clear, and an initial few dates between these communities have gone well, the idea of ‘integration’ still feels like a big leap to ‘forever together.’"

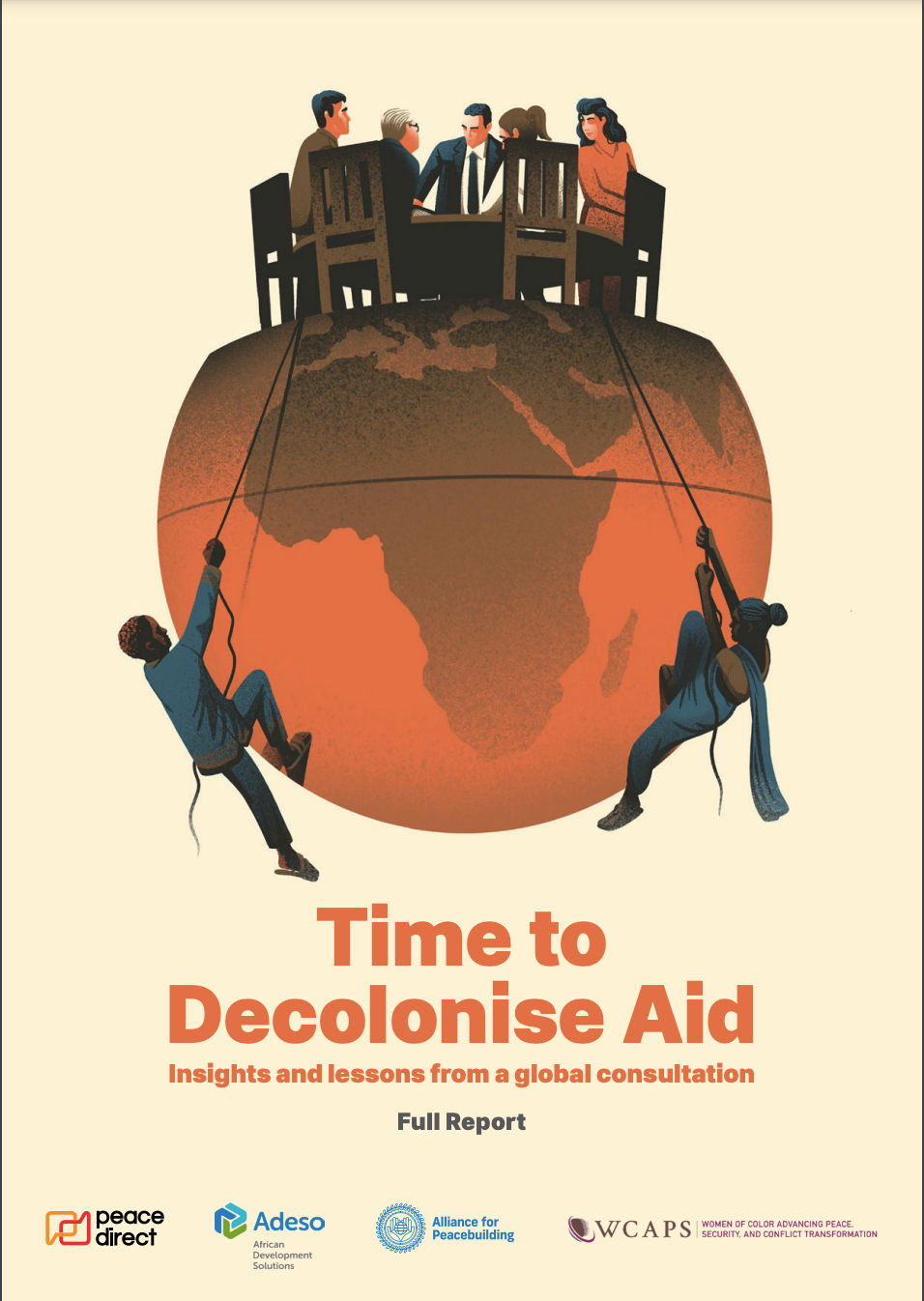

The peacebuilding field aspires towards realizing local ownership in practice, decolonizing aid and radically shifting current unequal local-international power dynamics. Although not yet universally adopted, some international peacebuilding agencies have taken real steps in this direction, actively engaging in dialogues and program models with local actors and international donors to define new approaches. While Breaking the Vicious Cycle rightly notes peacebuilding’s localization agenda, it does not reflect on whether the anti-corruption field has similar—and more importantly—compatible ongoing discourses and agendas. Nor does it reflect on the complications for any integration “if” addressing the international-local power imbalance is not a parallel thrust in the anti-corruption community. If the two communities of practice aren’t aligned on the ethics of unequal power dynamics in international aid, achieving integration seems difficult to reach.

In the end, it’s about “who” makes up the community to be integrated and how to involve them up front in defining what the agenda will actually be. Getting clearer on the “who” means putting local peacebuilding and anti-corruption actors at the center of processes to define any joint approaches, priorities and ethics. It may mean that the very meaning of key concepts like transparency, accountability and integrity would need to be explored and defined across settings with a wide range of local actors—and not taken as widely accepted universal “givens.” Any effective closer relationship would have to get to these deeper level questions and processes around the “who.”

HOW would an effective courtship go?

We believe it’s best to start small and iterative by making concrete evidence-based shifts and learning as we go along the lines of adaptive management approaches. If not, the risks of a costly divorce are high—the report clearly lays out where the tools and approaches used by the anti-corruption sphere could risk damaging the access and leverage of peacebuilding actors (and presumably vice versa). The report also identifies the gorilla in the room: both arenas risk being instrumentalized by geopolitical interests and international actors who play outsized roles in both peace processes and in grand corruption in conflict affected states. Both fields rightly seek to avoid being discredited as a tool of such powerful state interests.

What if we simply asked “what is the most effective relationship and why”? To answer this, we wondered if focusing on key elements of programming through a context-specific lens and collecting the experience first would be helpful.

1. What is a conflict analysis methodology for selecting intervention points that reduces conflict while not buttressing corruption in the short or long term?

Given that corruption comes up in plenty of conflict analysis frameworks, inclusion is not the issue; rather, this dialogue would explore what is included, why and how this informs program design. We need to get specific about the type of corruption that is problematic and how it relates to either stability or instability! For instance, generically including corruption is unlikely to be helpful as corruption is a basket of different behaviors ranging from political interference to ‘fee for service’ acts by low-ranking civil servants.

2. How would peacebuilders need to alter their programmatic theories of change in order to better advance anti-corruption ends?

Agreement on broad goals of peace, justice, or equity would seem fairly easy to achieve between the two fields. It is when we get to the concrete assumptions found in the proverbial if X then Y because Z that we can see if each field is actually seeking the same thing.

Zeroing in on specific theories of change also offers the two fields the opportunity to innovate. The anti-corruption field increasingly recognizes the need to engage with power and politics in its programming, but struggles to crack the code on how exactly to do this. Yet power and politics is the bread and butter of peacebuilding, so its conceptual frameworks and approaches may help.

3. How would peacebuilders need to change the way they work or the “means” they use in order to advance anti-corruption?

We spent some time circling around the idea that maybe it is also about the way work gets done, i.e., the “means” used? How to get to greater mutual understanding, better relationships and ultimately, yes, “trust” in each others’ ways of working? After all, some of the approaches seem contradictory. With peacebuilding it’s often inclusive, confidential dialogue and creating ‘safe space’ for all—even wrongdoers—which seems at odds with much of a classic anti-corruption toolkit, e.g., transparency, ‘naming and shaming,’ excluding wrong-doers, and legal prosecution.

And what about expectations for “transparency” to be modelled in peacebuilding? Many projects, for instance, feel they must initially downplay explicit peacebuilding goals in order to engage people from hostile opposing communities in common activities, so might expectations of full transparency be difficult? What about when entrenched corrupt practices by governments or police make basic operations impossible without agencies to some degree “playing by the local rules” (e.g., equipment is unjustly held in a port or permits are ‘delayed’ until bribes are paid)? What are realistic solutions in these contexts for vital peace efforts to proceed?

By the end of our walks along the river, it was clear that these families had much more to discuss and there would be great value in doing so. Getting to know each other in a way that:

clearly lays out what each these fields entail in order to identify where they are compatible, where they are not, and where innovation may be a possibility

establishes who exactly will decide what this relationship looks like

enables practical in-depth discussion and evidence-based learning, grounded in context, around real programming questions.

Whether a marriage (AKA, full-on integration) would result, mind you, was still a wide-open question but at least we agreed how to find out.

Dr. Lara Olson’s work has combined practitioner-focused learning, evaluation, and university-based teaching and research, with area expertise on the post-Soviet states and the Balkans. A developmental evaluator with civil society peacebuilding programs in the Caucasus since 2014, she recently was part of an evaluation of the OSCE’s dialogue projects in Ukraine. Her research has focused intensively on peacebuilding coordination and complex systems, and she co-directed a joint University of Calgary & Institute of World Affairs project on mission-wide coordination effectiveness, with Afghanistan, Kosovo, and Liberia cases. While based in Cambridge, Massachusetts in the 1990s, Lara directed the original phase of the Reflecting on Peace Practice project as well as worked with the Harvard Program on Negotiation, the Consensus Building Institute, and the Conflict Management Group on research and practical interventions to address ethnic conflicts in the post-Soviet states, most extensively on the Georgian-South Ossetian conflict. She recently completed her doctorate in International Relations at Oxford, and has an M.Sc. from the London School of Economics, and a B.A. in Political Science from UBC in her hometown of Vancouver.

Cheyanne is the Executive Director of Besa Global and the Co-Director of the Corruption, Justice & Legitimacy Program. As a scholar-practitioner with a lifelong interest in governance processes that have run amuck, she has significant experience working on peacebuilding, corruption, accountability and programmatic learning across the Balkans and West/East Africa. For fifteen years, Cheyanne taught program design, monitoring and evaluation in fragile contexts at the Fletcher School/Tufts. Prior to that she was the Director of Evaluation for Search for Common Ground and Director of Policy at INCORE. She has had the privilege of working in an advisory capacity with a range of organizations such as ABA/ROLI, CDA, ICRC, IDRC, UN Peacebuilding Fund and the US State Department. She can be commonly found in the Canadian Rockies with her fierce daughters and gem of a husband.

Comments